Previously on this website, the nature of hydrofracking has been briefly discussed in the hopes of offering our readers a balanced view of the practice. I have tried to present both the benefits and drawbacks of the practice in an objective view, and hope that the readers have taken the time to continue to educate themselves as to the subject, and form their own opinions.

Today, I would like to touch base on the subject of water usage in the hydrofracking procedure. According to information compiled by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, nearly 92 billion gallons of water were used nationally between the January of 2011 and February of 2013, with each well utilizing approximately five million gallons of water.

Today, I would like to touch base on the subject of water usage in the hydrofracking procedure. According to information compiled by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, nearly 92 billion gallons of water were used nationally between the January of 2011 and February of 2013, with each well utilizing approximately five million gallons of water.

No matter how you look at it, that’s a lot of water, and it has to come from somewhere.

According to the Ohio EPA fact sheet concerning the potential water sources for hydrofracking, dated 2014, potential sources of hydrofracking water can include both potable and non-potable sources — which means those five million gallons per well can be obtained from any type of water source, regardless of whether or not it is a viable and safe drinking water source. However, if the removal of water from the source would adversely affect the surrounding land owners or land use, civil or litigation actions may be brought against the oil and gas companies to try to find a more balanced approach, one in which the needs of the majority are balanced with the needs of the individual or company.

Not surprisingly, the water used by hydrofracking is considered to be consumptive use — the water that is taken out of the system cannot be returned to it, and is incorporated with various hydrofracking fluids used in the process. Any leftover water, because of the chemicals used, must be treated as wastewater and disposed of in an approved manner.

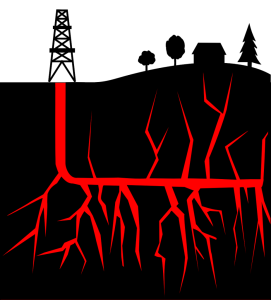

In addition to the removal of potable water from viable sources, there is also the potential for groundwater contamination during the process. In fact, the Ohio EPA has put together a fact sheet instructing potential worried well owners what to test for before and after the hydrofracking procedure in their area, and what contaminates to look for — including such things as barium, strontium, chloride, calcium, benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, xylene and methane to name a few.

In addition to the removal of potable water from viable sources, there is also the potential for groundwater contamination during the process. In fact, the Ohio EPA has put together a fact sheet instructing potential worried well owners what to test for before and after the hydrofracking procedure in their area, and what contaminates to look for — including such things as barium, strontium, chloride, calcium, benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, xylene and methane to name a few.

Thankfully, since the laws were strengthened in 1985, there has been a significant decrease in the number of potable wells that have been impacted by oil and gas drilling of any kind, but impacts still occur. In addition, Section 1509.22(F) of the Ohio Revised Code provides the Ohio Department of Natural Resources with the authority to require that the oil and gas well operator replace the water supply of a private or public well that has been shown to be impacted.

In addition, a recent Ohio Supreme Court ruling concerning a case where the local community had banned hydro-fracturing made it clear that the only government department with the authority to take such action was the state itself in the form of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

So what does this all mean? Is hydro-fracturing a viable and safe option, considering the impact it has on the amount of water available for use, as well as its potential impact on the availability of safe drinking water? Does the potential economic and energy advantages outweigh the risk?

In truth, each individual, and ultimately the community as a whole must weigh the potential risks against the potential benefits and decide for themselves. Some states in the area, such as Ohio and Pennsylvania have sought to welcome the use of hydro-fracturing, while others, like Maryland, have struggled to keep hydro-fracturing at bay.

What are your thoughts? Are the benefits of hydrofracking worth the potential impact to our water resources?

What are your thoughts? Are the benefits of hydrofracking worth the potential impact to our water resources?